“Good Talk uses a masterful mix of pictures and words to speak on life’s most uncomfortable conversations.”—io9 “Mira Jacob just made me toss everything I thought was possible in a book-as-art-object into the garbage. Her new book changes everything.”—Kiese Laymon, New York Times bestselling author of Heavy. Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations by Mira Jacob, is an unusually gratifying, smart and fly-ass curation of days and words and moments that all somehow coalesce in an almost 3-D kind of way.

The writer and illustrator on the early stages of drafting, interracial parenting, and creating a visual language for herself.

I was introduced to writer Mira Jacob through the raconteur essayist Garnette Cadogan, who invited us to do a conversation for LitHub, “Our Kids, Their Fears, Our President?,” in November, 2016 about how we were discussing the presidential election with our kids. That seems about two millennia ago, though it’s only been two and a half years. At the time, Jacob was working on developing a graphic essay that had gone viral on Buzzfeed, “37 Difficult Questions from my Mixed Race Son,” into a book,Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations (One World), which was just released with much deserved fanfare. Jacob presents difficult conversations about race and ethnicity with her young son, Z., and with her own parents (starting from when she was a child), lovers, teachers, and friends. What results is a complex and evolving portrait about the absurdities and realities of growing up as a person of color in a land built on the myth of white supremacy. We spoke again, via email, about how she crafted her unusual book.

—Emily Raboteau

Emily Raboteau How did Trump’s election change this project?

Mira JacobIt catalyzed and crystallized it. Writing this felt urgent. The home that once held my body and my son’s body had become, and continues to become, increasingly hostile. Every day of writing this felt like I was trying to find us a bridge to another place, a place we could catch our breaths and grow into the people we want to be instead of the ones this country is trying to turn us into.

ER I recently came across a piece on LitHub about how drawing makes better writers: “How Learning to Draw Can Help a Writer to See.” Do you think this is true?

MJ I think the movement involved with drawing, of allowing a shape to turn and morph on the page, to become itself instead of what you thought it should be, is great preparation for that moment when you write the story that is perfect in your head but comes out small and flawed and flimsy on the page. I didn’t know this when I first started writing. I thought I was just failing. No one told me that you have to work and rework that story to let it become the most interesting version of itself. But with drawing, that understanding is inherent to the process.

ER You shared on Instagram that VH1’s “Pop-Up Video” was an inspiration for the design and aesthetic of Good Talk. What are some other unexpected influences on your graphic memoir?

MJ A few things come to mind:

Paper doll books. I always loved looking at the way the dolls were posed on their own, and then watching each pose take on different meanings with the change of setting and clothing. One of the things I realized early on is that if I drew each of us as paper dolls and did not change the facial expressions to account the emotions in any given scene, the reader would have to hold the emotions that our faces did not. It was such a relief. It gave me real psychic freedom from performing racial pain for a country that is largely unmoved by it.

’90s zines. I read every one I could get my hands on back then—Bitch, Bust, Bikini Kill, all that Riot Grrrrl stuff. I loved the way they felt smashed together with urgency, the headlines and illustrations and little boxes of text all adding up to a rush.

The podcast “Still Processing.” Whenever I felt like I had something I could not possibly write, I would listen to Jenna Wortham and Wesley Morris wade into a difficult conversation with love and patience for each other, and it made me realize how important it was to believe in us—the many of us out there ready to talk about and hear and hold onto the hard parts.

Chani Nicholas’s horoscopes, which are always written with an eye toward looking at your life from three thousand feet away, understanding how your actions impact society, and then getting back into your body to change real shit.

This video of writer Maud Newton’s puppy carrying around a huge hunk of a paper with some serious determination. What is she going to do with it? Where is she taking it? She has no idea. I felt the same way writing the first draft of this book. I watched this video to keep me in a decent mood about it.

ER Your reply reminds me of Adrienne Kennedy’s marvelous scrapbook memoir,People Who Led to My Plays. Do you know it?

MJ No, but I have just looked it up. It looks incredible. Tell me more.

ER It’s exactly what she pronounces, a scrapbook of people who led to her plays, chronologically ordered as she grows up. She includes images and text about the images. Jesus might show up on the same page as Frankenstein’s monster. Jessie Owens is in there, along with paper dolls. Her influences are both wide-ranging and incredibly specific to her experience—her mother, her father, her teachers, her president, the movie stars of her era. I see you using some of the same techniques. For example, you show Michael Jackson as an influence on your son and as a window into tough conversations with him about racial politics. Tell me, how did you square the ethics of exposing the bigotries of real people in your life, some of them members of your immediate and extended family?

Good Talk Mira Jacob Chapter Summary

MJ I live with and love many of the people in this book—especially my family. I wrote everything I needed to and then went back and edited it down to just the essentials. I asked myself repeatedly if I was writing for clarity or vindication, and if the answer was the latter, I cut it. I’m aware of the climate we’re in and how easily internet mobs are mobilized, so I know that writing any of this is a risk. And it’s terrifying. But not more terrifying than some of the ways I have mishandled other people’s lives and dignity. Not more terrifying than living as a brown mother of a brown boy in a country that is routinely violent to people of color. Not more terrifying than being told you are loved by the same white relatives who are helping turn that country even further against you.

My goal in writing this book was to hold myself as accountable to my own mistakes as I held anyone else to theirs. To that extent, there is so much in here that people can dislike me for, and it is their right to do so.

ERI had a writing teacher tell me once that in nonfiction you need to be as hard or harder on yourself as you are on anyone else. That accorded with me.

MJAbsolutely. It was essential for me to remain mindful of people’s boundaries, their privacy, to the extent that I could. In the case of my in-laws, they have been out on corners holding signs for Trump, and continue to stay loyal to him—so I didn’t feel like I was exposing anything about them that they did not expose about themselves. I did not write down many of the more painful things that they’ve said to me in private—things they would never realize were upsetting, in the same way that they don’t realize how their vote for an openly racist president has hurt our relationship.

EROne of the most emotionally powerful parts of your book is when your white husband asks you about you and your brown son, “You think I don’t know you guys?” after your son wonders if he’s afraid of the two of you. It’s a question that you don’t answer in the moment, and it’s a moment that you repeat.

MJIt’s an unanswerable question, one that underpins my marriage, my parental life, everything. There are things he simply can’t know about life in a brown body. In terms of writing about the interracial friction in my marriage, my husband was weirdly supportive. I say weirdly because I didn’t expect him to be so sanguine, and, in fact, there were points at which he hasn’t because he’s an intensely private person. But he’s also an artist, and at the end of the day, he would always come back to me saying, You’ve got to write the truth, and we will deal with the fallout. This was helpful because it let me bust through the myths America has around interracial marriages—that they are either full of deep, constant, unwavering understanding, or that they are based on one partner or the other secretly hating themselves and their race, and therefore subjecting themselves to a relationship that cannot possibly meet them. He met me. He continues to meet me.

ERAs the post-Loving child of an interracial (black/white) marriage, I found it at times insufferable to be treated as a metaphor for racial healing, so I appreciate your honest depiction of the friction, and even the loneliness, within the marriage.

MJThat’s infuriating to me—a country needing a child to be a human bandage over a wound they can’t even look at. I’m sorry. You deserved better than that.

ERThank you. I agree, even as I understand the human need for metaphor. How does Z. feel about his representation in the book?

MJHe likes it right now. He likes it when I read our conversations back to him, and he laughs at them sometimes. But I’m also preparing myself for the day that he doesn’t. He’s a whole human, and I think sometimes people forget that about kids. They want them to be simple, innocent, unchanging. I worry about readers who meet him needing him to perform this version of himself forever, and about the toll that might take on him. Or some future tabloid headline: SweetKid in Book Makes Monstrous Blunder! He’s allowed to grow, you know? He’s allowed to feel his way through this just like the rest of us. I’ve told him that he’s much more interesting than anything I could get on these pages, and that he’s allowed to just walk away from anyone who needs him to be less, including me.

ERDoes he still love Michael Jackson? If so, I have a rare picture of MJ for you to show him.

MJUgh. We are in a really raw place with this. I talked to him recently about some of the allegations because I knew he was hearing little things at school and I wanted him to hear it from me, at a moment when he didn’t have to worry about what his face did, what his heart did. And it was just … awful. He had put together so many of the clues, so he was on the right track, but he didn’t know the victims were kids. I saw it register in his eyes and felt terrible. He was so angry. So hurt. He was mad at Jackson and mad at Joe Jackson and mad at men. It was a lot.

ERYeah. I’m still grappling with the truths exposed by Leaving Neverland, which wasn’t about Michael Jackson so much as about patterns of child sexual abuse and the everlasting ripple effects of trauma.Here’s the picture I wanted you to share with Z. Michael’s seventeen years old in this rare photo, taken in Amsterdam. It’s hanging in our hallway, life-size, like a portal into another dimension. I’m struck by how happy he looks, how free. But he felt neither of those things in his body.

MJThis is a beautiful picture. It’s also painful to see, to know all the hurt he was holding and would eventually inflict on others.

ERMorality aside, nobody’s calling his artistry into question. As for impressive artistry, what were the biggest process-oriented differences for you, between crafting this narrative and writing your novel?

MJOof, so many. Technically, I had to teach myself how to use four different kinds of software and how to draw on a computer, which can be weirdly soulless. You know this from your gorgeous photographs of decomposing posters all over the city—paper has such a personality.

Photo by Emily Raboteau, “Two Degrees of Warming,” from On the Blue Line, 155th St. C train station, upper mezzanine. December, 2018

Screens, not so much. I had to find my way back to my own style when I didn’t have anything to rub up against. It took a while.

Emotionally, I just had to really get down with being in the abyss for a while. I was creating a visual language for myself, and there was no one else on Earth that knew it. I was learning so many things every day it felt like my brain would break. I was also trying to be a loving wife and mother and daughter and friend and not always being great at that. I cried a lot writing this book, convinced I had fucked over every person in my life in different ways. I missed a lot of events, I didn’t respond to a lot of emails, I let go of a few beloved but toxic white friends when I realized their capacity to engage with me was only ever going to be in ways that centered their feelings over mine. It was fucking lonely.

I just looked back at the question and realized you asked about process. It’s probably telling that I don’t have a craft answer here. The craft part of this was the one place I felt stable.

ER But the toll paid off! And Good Talk is now being developed for TV. Will the TV show be animated? What’s that writing room and production process going to look like?

MJ Not sure about either of those things since it’s in early stages. All I can say is I am excited to figure out another way to communicate, no matter what that looks like.

ER I am teaching Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home this semester in my “Nonfiction Fringe” class at City College (along with Good Talk and People Who Led to My Plays and H is for Hawk and Bluets and a bunch of other fabulous hybrid texts by women) and using it as a tool to teach my students about precision and compression. That is, how much Bechdel can do, for example, by showing what’s playing in the background on radio or TV to contextualize her drama. In terms of visual storytelling, talk us through a pivotal panel in another graphic memoir that inspired and crystallized for you what you can do in this format that you can’t do in any other, and then where you applied the same or similar technique in a panel of yours.

MJ This is among the early pages of Emil Ferris’sMy Favorite Thing is Monsters.

The book is glorious. My favorite thing about her hatch-work illustrations is how you can feel the time spent inside the drawing, the beats of the author thinking as the protagonist, and the protagonist thinking like a detective. Every delineation of light and shadow becomes a clue. This is hardly the most spectacular spread in the book, but I love it especially for its simplicity, the way she just lets all those lines spill from brain to page. I love the deconstructed dialogue bubble and the ear pitcher in the margin and the vulnerability of looking at an adult from this angle. I forgot, until I saw this, how well we get to know the undersides of our mother’s faces, and how much they tell us about what our future holds.

ERYes, our mother’s double chins.

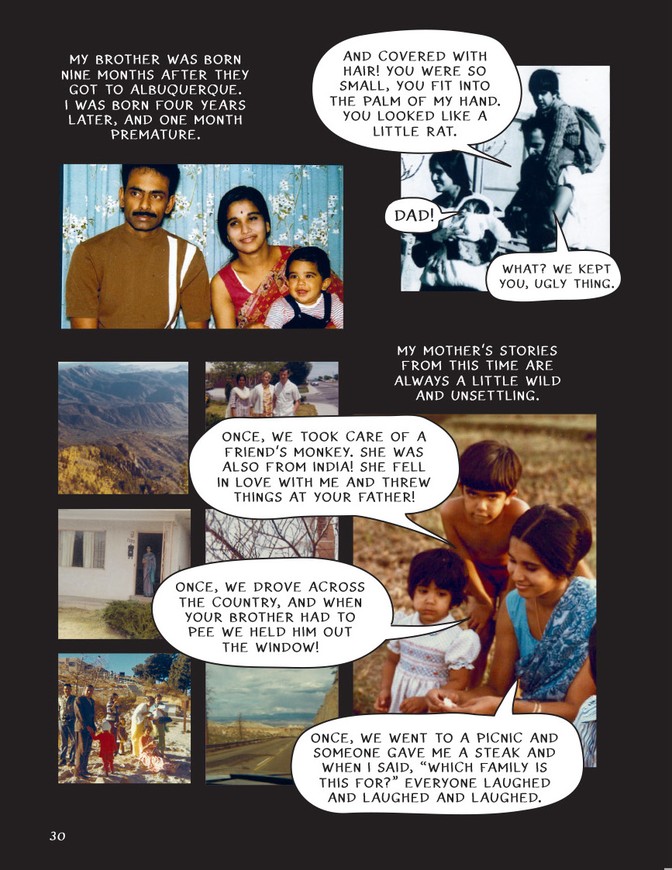

MJ In my own work, when I was writing a chapter on my parents coming to New Mexico in the 1960s, I realized I wanted to include actual pictures of them but couldn’t figure out how to include the drawn pictures of them talking about themselves. Early spreads were a mess—too many characters, too much competing information. Finally, I just drew the dialogue bubbles coming directly from their photographs—it was hilarious how quickly and cleanly it solved the problem.

ERI envy this precision. On the topic of motherhood, how has parenthood adjusted your relationship to your art? Obviously, it’s central to this project.

MJIt has made me furious. I realize no one wants to hear that, but it’s the damn truth. I see the way men make time for their art, how society and family structures and institutions applaud and encourage it, and it makes me livid. I have to work four jobs and deal with a seismic amount of guilt just to get to part one of my process. I say this as a person with a supportive partner, as a person with a relatively enlightened community behind her. Every day I have to reset people’s expectations of what they will allow a brown woman to dream possible for herself as an artist. Every. Damn. Day.

Motherhood has also made getting to my art more important than ever. I want my son to see what this brown woman dreams possible for herself. I want him to take in what that means for his own brown body, and his own sense of manhood.

ERGood Talk strikes me as a distinctly post-9/11 book about fractured identity. What other NYC books and authors do you consider this work to be in dialogue with? Same question regarding other South Asian artists and artworks, and other books about mixed race identity.

MJOh, wow. What a gift of a question. I almost don’t know where to start. Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go for its ability to walk sure-footedly between the familial and the political. Arundhati Roy’s numerous non-fiction essays and ability to keep writing about what mattered to her, always. Jenny Zhang’s Sour Heart for the potent rage of what has been made invisible. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me for how to write toward the terror and vulnerability of parenthood. Tanwi Islam’s Bright Lines for the constant reminder that we are allowed to write all of our many selves. Kiese Laymon’s Heavy for sitting with shame long enough to let it become something entirely else. Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel for taking a form and bending, splitting, and reopening it in wild ways. Kaitlyn Greenidge’s essays and her novel We Love You, Charlie Freeman for looking backward and forward with equal vigor.

ERWhat would you, adult Mira, tell child Mira Jacob about being American in response to the loaded moment in the book (another favorite of mine) when your teacher insisted that this was what you were and always will be: an American?

MJOh lord. Can I just tell you I was nineteen and super high when I finally, FINALLY realized that Ms. Morrell, the teacher that told me that, wasn’t mad at me? That she was, in her way, fighting for me? I would probably try to tell kid Mira that sooner. That this woman is loving you to the best of her ability, and being American can still be every bit as complicated as you need it to be to hold on to all of you.

Good Talk Mira Jacob Excerpt

Emily Raboteau is the author, most recently, of Searching for Zion (Grove/Atlantic), winner of an American Book Award. A professor of creative writing at the City College of New York, she’s compiling a book of personal-political photo essays mapping public art, public space, climate change, and parenthood in NYC, entitled: CAUTION.